Food for thought

Urban lakes contaminated with arsenic pose consumption risk

By: Brooke Fisher

Photos by: Julian Olden, Dennis Wise and Olivia Hagen / University of Washington

Top image: CEE associate professor Becca Neumann tosses a crayfish trap into Lake Killarney.

After analyzing the human health risks of eating aquatic organisms from arsenic-contaminated urban lakes in the Puget Sound lowlands, UW researchers have a menu of concerns. Specifically, they found that consuming certain aquatic organisms in the lakes elevates cancer risk.

“The idea was to focus on organisms that people might eat, so we studied snails, crayfish and sunfish,” says CEE associate professor Becca Neumann. “What we are seeing is elevated levels of arsenic in them.”

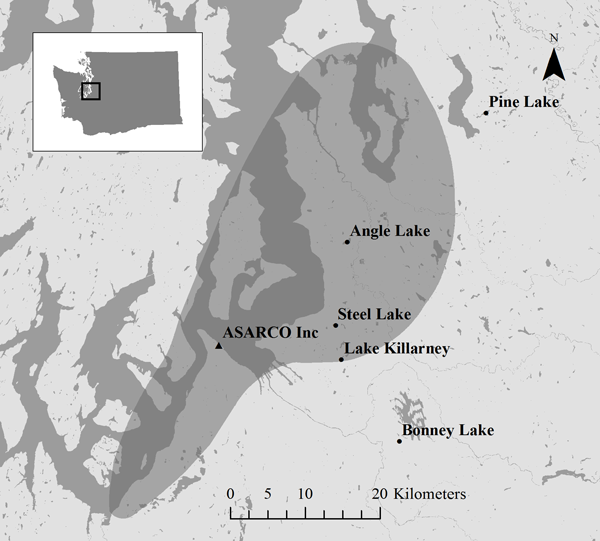

Four small public access lakes with varying levels of arsenic contamination and depth were selected for the study: shallow lakes Bonney Lake, Steel Lake and Lake Killarney, and Angle Lake, which is deeper than the others. All are located downwind of the former Tacoma-area ASARCO copper smelter, which pumped waste byproducts that contained arsenic and lead into the air for 96 years before ceasing operation in 1985.

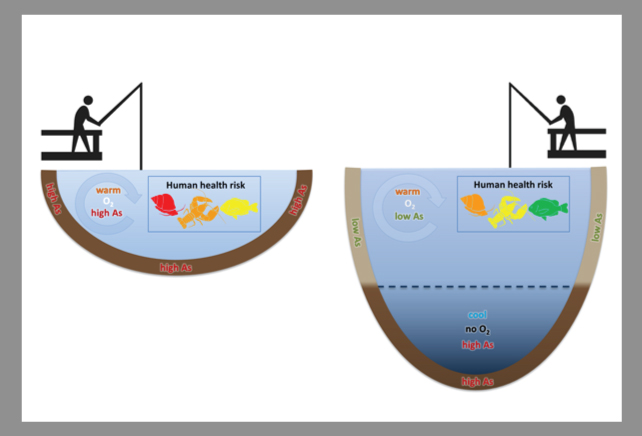

Overall, the researchers found the shallow lakes had proportionately more arsenic in the sediments near the shore when compared to the deeper lake and that near-shore sediment and shallow water arsenic concentrations controlled the amount of arsenic in tissues of the snails, crayfish and sunfish. Lake Killarney, a shallow lake with the highest concentrations of arsenic in near-shore sediments, posed greatest human health risk. The study builds on research conducted two years ago, when the researchers discovered that the water of some shallow lakes contains surprising levels of arsenic, due to unique characteristics that facilitate the movement of arsenic from lakebed sediment up into the surface waters and near-shore areas where the aquatic food web resides.

Although it’s currently unknown how many people may be eating from the lakes, the researchers speculate that some populations may be fishing for subsistence reasons rather than sport. Many states, including Washington, don’t require a permit to harvest snails.

“The population we see out there fishing on a regular basis is more diverse than the nearby homeowner populations,” says Jim Gawel, associate professor of Environmental Chemistry and Engineering at UW Tacoma.

“There are fishermen who come out when they stock trout in the lakes, but there’s also a population that fishes throughout the year.”

Supported by UW’s Superfund Research program, the research team includes scientists from UW Civil & Environmental Engineering, UW School of Aquatic & Fishery Sciences, UW Tacoma Environmental Sciences, and Dartmouth College Department of Earth Sciences.

Left: Associate professor Rebecca Neumann places dog food, commonly used as bait, in a crayfish trap. Top Right: Associate professor Rebecca Neumann places dog food, commonly used as bait, in a crayfish trap. Bottom right: Setting crayfish traps in Lake Killarney.

Arsenic exposure and cancer risk

Arsenic enters the aquatic food chain primarily through diet. This occurs when plankton ingest arsenic, mistakenly thinking it is a nutrient, before being consumed by other organisms. Arsenic diminishes in organisms as it moves up the food chain; however, this means that eating lower on the food chain is especially problematic.

“Snails have a lot of arsenic in them, as they are crawling on the surface of the lakebed and are grazers,”Neumann says. “With snails, we found that in all of the contaminated lakes there was increased cancer risk.”

Snails on average contained the most arsenic of the three species investigated. Concentrations of arsenic in snails and crayfish from Lake Killarney were higher than all other lakes in the study. Arsenic concentrations in fish were also highest in Lake Killarney, followed by Steel Lake. The researchers calculated that consuming aquatic organisms from Lake Killarney resulted in four to ten times greater health risk compared to organisms from the deeper Angle Lake, which has similar arsenic concentrations in sediments from the deepest part of the lake.

According to the researchers, cancer risk is determined by the aquatic organisms’ concentration of inorganic arsenic, which is highly toxic compared to organic arsenic, and the quantity of organisms consumed by people. Based on their findings and WA Department of Health guidelines, the researchers advise no consumption of snails or crayfish from the arsenic-contaminated lakes in this study (Steel, Killarney, and Angle lakes) and no more than one meal per month of sunfish from Lake Killarney.

RELATED STORY

Lakes with a legacy

CEE researchers investigate surprising arsenic discoveries.

Next steps

The researchers are in the early stages of working with the Washington State Department of Health to explore issuing a fish consumption advisory for the lakes.

“The risk is there, but the question is how many people are at risk?” Gawel says.

If additional funding is approved, the researchers plan to survey lake users about their food consumption. They also hope to create a screening tool to quickly determine if lakes have concerning levels of arsenic in the food web, explore remediation technologies to remove arsenic from lakebeds, and investigate the impact of arsenic on aquatic organisms.

Community Collaborators

Community partners include Washington State Department of Ecology, Washington State Department of Fish & Wildlife, Environmental Protection Agency Region 10, Public Health Seattle/King County, King County Environmental Programs, City of Federal Way, Lake Killarney Improvement Association, Steel Lake Management District Advisory Committee and Angle Lake Shore Club.