By Brooke Fisher

Photos by John Guillote/OnPoint Outreach

Researchers explore the changing Arctic to improve climate models

Information about the role that waves play in the changing Arctic is rolling in, so to speak, after UW researchers spent a month at sea collecting data.

CEE faculty Jim Thomson and Nirni Kumar carry a SWIFT buoy across the deck of the research vessel Sikuliaq. Photo credit: John Guillote

“It was a successful trip. We measured some sizeable waves in November, which were very late in the season,” says principal investigator and CEE faculty member Jim Thomson, an oceanographer at the UW Applied Physics Laboratory. “The big waves were coming right at the coast and we think it’s changing the coastlines. It was remarkable to quantify that.”

The critical connection between melting sea ice, increasingly powerful waves and eroding coastlines has been missing from existing research in the Arctic. To help fill this knowledge gap, a team of researchers including Thomson and CEE assistant professor Nirnimesh Kumar set sail aboard the Sikuliaq, a research vessel from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, during the month of November.

“Before this we had no coastal observations and limited observations of waves and ice,” Kumar says. “The Arctic became a natural laboratory for us.”

By taking a closer look at the interactions between waves and sea ice and how they contribute to coastal erosion and flooding, the researchers hope to improve the accuracy of climate models, which can be used to inform more strategic climate policy decisions. The researchers are midway through a three-year Coastal Ocean Dynamics in the Arctic (CODA) project, funded by a $1 million grant from the National Science Foundation’s Office of Polar Programs.

Breaking a path through sea ice, the Sikuliaq prepares to set up for an ice station, which allows researchers to walk on the sea ice to collect samples and drill small holes in the ice to measure thickness. Photo credit: John Guillote

Pressing problem: Coastal erosion

The role that waves play in the erosion of Arctic coastlines is directly related to diminishing sea ice, which is at record low levels, according to the researchers. Sea ice has historically helped to protect the coast from powerful waves and turbulent storms, as more open water can lead to stronger waves as the distance over which the waves travel increases.

“The waves lose energy in the presence of ice when they interact, which is what we were interested in looking at,” Kumar says.

With stronger storm systems and associated waves becoming increasingly common, Arctic coastlines are eroding at rates of meters per year. Problems are already starting to impact the local communities that reside along the coast of Alaska, where subsistence hunting and fishing is prevalent.

As part of the project, a small team of researchers visited villages in Alaska last year to present their proposed research to the community and visit schools for K-12 outreach.

“Part of this is to hear from them about the changes they are seeing and learn from them,” Thomson says. “They [native Alaskans] talk about it all the time. There is a lot less ice and what ice remains is poor quality, not the kind of thing they can drive snowmobiles on or walk on. There are big changes in the fish that they see and trouble with subsistence hunting; it is affecting them in very day-to-day kinds of ways.”

Gathering data at sea

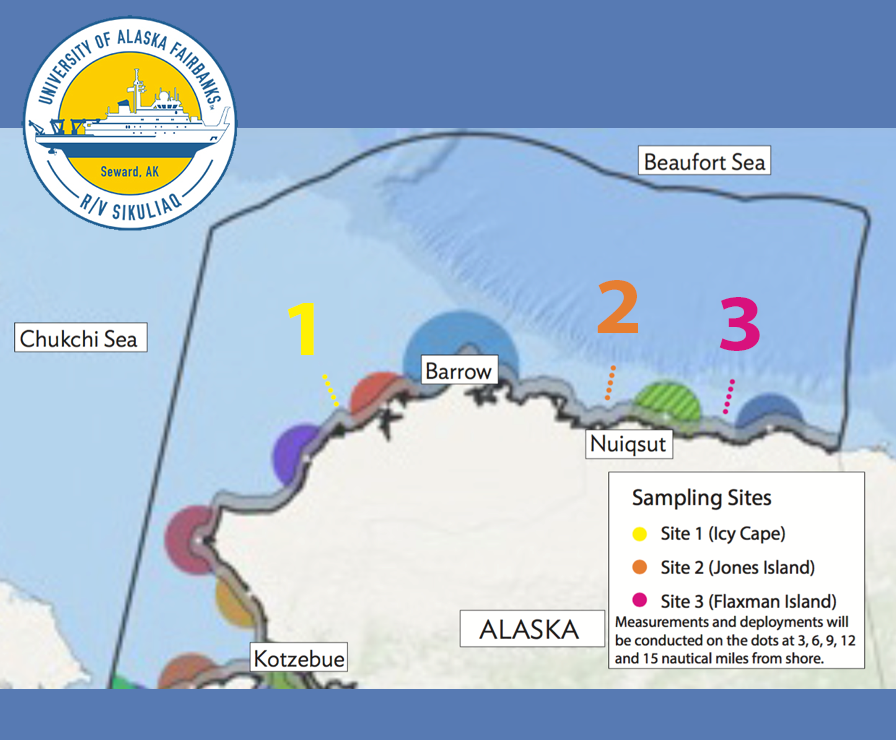

At the three sampling sites, researchers gathered data at specific distances from the coast. University of Alaska Fairbanks

With temperatures as low as minus 15 degrees Celsius, which is relatively warm by Alaska standards, the researchers collected data at three primary sampling sites: Icy Cape, Flaxman Island and Jones Island, located along the northern coast of Alaska where the Beaufort Sea meets the Arctic Ocean. At each site, samples were collected at specific distances from the coast.

“These sites were representative of the coastline that we want to study and the larger system,” Thomson says. “We were far enough away from subsistence hunting to not interfere with the local populations.”

The 10 members of the research team took turns being “on watch” for eight-hour shifts. They continuously monitored equipment and collected data using custom instrumentation, including autonomous buoys equipped with cameras, built by Thomson’s group at the UW Applied Physics Lab.

The researchers measured waves, turbulence and also quantified ice concentrations after scooping up pieces of ice from the water. They also collected data from satellite images that showed ice extent and collaborated with the U.S. National Ice Center, which provided daily updates on ice levels. Not surprisingly, conducting research in extreme conditions had its challenges.

“The buoys started to become ice balls,” Thomson says. “We had to do a lot of repeat deployments to de-ice them and put them back in the water.”

Forecasting the future

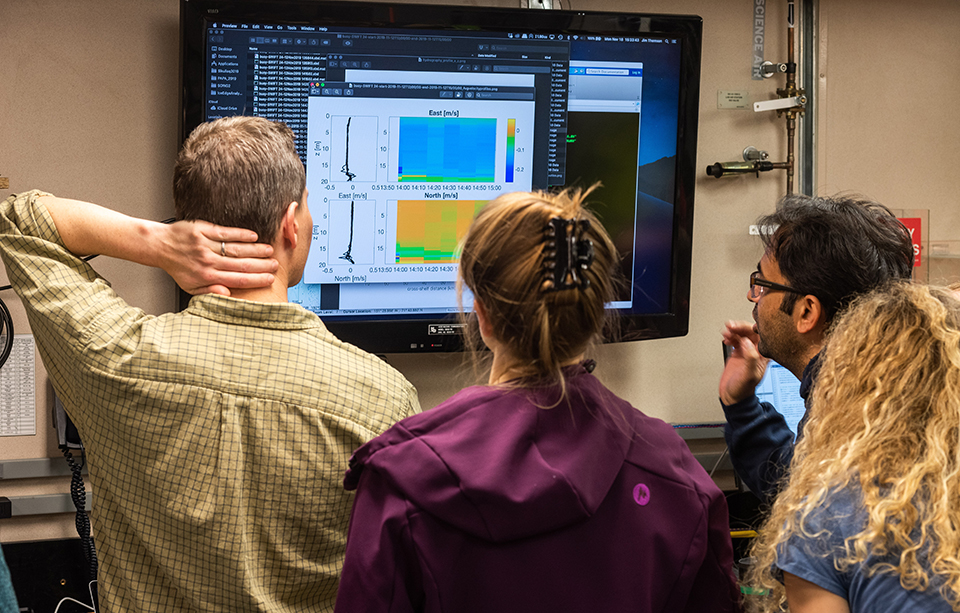

The CODA team looks at data collected by a SWIFT buoy drifting in sea ice. Photo credit: John Guillote

Back on dry land, the researchers are now analyzing data to better understand how waves gain and lose energy depending on ice coverage. They are contributing to an open source modeling system, using test cases for the northern Alaska coastal zone, that can be used to forecast future conditions and enhance climate scenario assessment and related policymaking.

“We will incorporate waves and ice and have that all in one framework to make better forecasts,” Thomson says. “These were treated separately in the past.”

In the fall of 2020, the researchers will shove-off again to conduct more analysis in the Arctic. Same ship, same region, different data.

The CODA research team on the deck of the Sikuliaq: John Malito (UNC), Jim Thomson (UW), Nirni Kumar (UW), Lucia Hosekova (UW), Lettie Roach (UW), Mika Malila (UW), Emily Eidam (UNC), Becca Guillote (OnPoint Communicatios) and John Guillote (OnPoint Communications), from left. Photo credit: John Guillote

Videos: During the research expedition, the researchers discussed the technology they used to capture data, offered tours of the ship and more via livestream events. Enjoy the videos.

Originally published February 24, 2020